2425 Wilshire Boulevard

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

AN INTRODUCTION TO WILSHIRE BOULEVARD IS HERE

Edwin Tobias Earl was born on a Sacramento Valley fruit ranch in 1858, and it was his hands-on understanding of California's agricultural bounty that contributed to the state's fame as an earthly paradise. Entering the shipping business at age 18, he looked for ways to market California citrus successfully as far as the East Coast and beyond. When the transcontinental railroads balked at building his invention of a combination ventilator-refrigerator car that could safely convey delicate produce through cross-country vagaries of climate, he began to manufacture it himself, eventually investing $2,000,000 in the venture. In 1897, with some of the enormous profits he realized, Earl hired East Sussex–born Ernest A. Coxhead to design one of the most artistic and distinctive houses ever built on Wilshire Boulevard. Coxhead, today associated more with the Bay Area, had arrived in Los Angeles in 1886, specializing in ecclesiastical commissions in his early California years. (One of his rare Southland residences remains at 127 East Adams Boulevard.) Contrived in the architect's signature shingle style to artfully suggest rusticity despite its size, a fire causing extensive damage as it neared completion in the summer of 1898 sent Coxhead back to the drawing board. A revised scheme now incorporated clinker brick walls; it was finished in 1899 and stood at the northeast corner of Carondelet Street in Gaylord Wilshire's original subdivision for many years, until, ironically, an art school demolished it. The Otis Art Institute (today the Otis College of Art and Design), having occupied Harrison Gray Otis's old house next door at 2401 Wilshire since after the General's death in 1917, acquired 2425 in 1938; both houses were gone by the fall of 1957.

|

| The face of confidence: Edwin Tobias Earl, circa 1895 |

Only occasionally does one run across a native Californian among the builders of significant early-20th-century Los Angeles houses. While all of them were by and large men of significant entrepreneurial talents, few seem to have ever combined the imagination to see not only opportunity but to actually invent three-dimensional ways to further exploit it. Perhaps behind it was the drive of Edwin's father Josiah; like many men drawn west by the Gold Rush, the elder Mr. Earl realized after arrival that the chance to make a fortune lay more in fields ancillary to panning, or in making the most of other natural riches there for the taking in California, riches beyond the imagination of Easterners who were not present to see the bounty for themselves. Josiah moved around the state as a freight hauler, later settling near Red Bluff to raise fruit and deal in lumber. After marrying another Ohio native who'd come west in 1852, two sons were born, the eldest, Edwin Tobias, at Antelope in Sacramento County on May 30, 1853. Before long, Josiah moved the family to Inyo County on the east side of the Sierra Nevada, continuing fruit farming while swapping lumber sales for silver prospecting. Brought to their knees by an earthquake in 1872, the Earls moved to Oakland, Josiah becoming a merchant and Edwin a student. Leaving high school prepared by the example of his father and with his own particular itch to succeed, Edwin, according to the estimable and intelligent blog Carbon Canyon Chronicle, "became one of the earliest forwarding merchants to send oranges from Southern California on the newly completed direct transcontinental railroad (the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe route, specifically), with the first shipment leaving from the orange boom town of Riverside in early 1886. The following year, he created the Earl Fruit Company to manage the handling of oranges for transport."

The rest of the story could not be better told than by the Carbon Canyon Chronicle, which continues:

"There was, however, an important inhibitor to the success of orange exports long distance: the tendency of the fruit to either freeze with existing ventilated box cars or to be lacking in ventilation in all-refrigerated cars. Earl's solution, developed in 1890, when he was but 32 years old, was the C.F.X. ventilator-refrigerator car, used by the Continental Fruit Express company, which Earl formed to handle...shipments by the specific car he developed.... After a decade, Earl was bought out by Chicago's mighty food-producing giant, Armour and Company, for some $2.5 million.

"Earl almost immediately took some of his fortune and bought the Los Angeles Express, a newspaper of about 30 years' operation in the city, and he joined the ranks of powerful publishers...like Harrison Gray Otis and Harry Chandler of the Times and William Randolph Hearst of the Examiner (later the Herald-Examiner)."

|

| The parties at 2425 Wilshire were never "rag tag and bobtail" affairs, nor were the neighbors riffraff. Even between his wives, Edwin T. Earl entertained the biggest names in town, some of whom lived nearby. The Sterrys were at 2607, the Otises next door at 2401. Before Earl's Express began to challenge Otis's Times, the latter paper mentioned E. T. in a positive light, such as on March 12, 1902, above. |

Entering the newspaper business was bound to rankle Earl's next-door neighbor, Harrison Gray Otis of 2401. As the 1900s unwound, the new publisher's Good Government ("goo-goo") zeal caused his print rival to vituperate endlessly as the editors of the Express pushed for political reform. Revealing more of his own megalomaniacal tendencies than any particular crimes of Earl's, the famously childish Otis neglected no chance to describe the upstart negatively. E. T. was by turns "ungrateful," "spiteful," a "fake reformer," a "vulture," and even "afflicted with distress of the mind." Referring to "E. Toopius Earl," the Express itself was described by the Times as a "rag tag and bobtail" enterprise. In 1909, the Christian Science Monitor, among other publications less dyspeptic than the Times, shed praise on Earl for his successful campaign against municipal corruption. Otis, who died in July 1917, would not give up his petty sniping even from the grave; on the following November 27, just weeks before Earl died, a Times editorial called Earl a "skunk" and compared him to the German kaiser.

And yet Otis's sputtering appears to have been at least somewhat for show, and, no doubt, to sell newspapers. The Chinatown facets of the history of Los Angeles came together with Earl's partnership in land acquisitions, most notably in the San Fernando Valley—with none other than Harrison Gray Otis, among others. Per the Carbon Canyon Chronicle, Earl and Otis joined "...Moses Sherman (Sherman Oaks developer), Leslie Brand (Title Guaranty and Trust Company executive and Glendale's Brand Library namesake), and railroad magnate Henry E. Huntington...in the San Fernando Mission Land Company, incorporated in 1905...which benefited by the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct eight years later. It was widely claimed that, because Sherman was a member of the Los Angeles Board of Water Commissioners, there was inside information he passed on to his associates so they could buy the land cheap[ly] before word of the aqueduct project became public and sell dear for a $5 million profit."

There was also the tiny fact that much of the Los Angeles press was owned by men in on the deal—it was a simple matter for editors to scare Angelenos into believing that without the aqueduct, tumbleweeds would soon dance in the streets. Edwin T. Earl may have been a champion of civic reform, but Gilded Age prerogatives were still in full bloom. Cronyism and back-room deals ruled the city even if the public could be made to believe that, for example, Earl and Otis were at odds. They were very much next-door neighbors.

During the years of at least partially mock discord, the Times rarely mentioned E. T. Earl in a positive light, even ignoring him in its voluminous coverage of Society. The ladies, of course, were not to bother themselves with the administration of power, except among their fellow matrons. The second Mrs. Earl was mentioned frequently as hostess at 2425 of endless luncheons, bridge parties, and other entertainments. The distaff side's right to vote came precociously in California in 1911, in part because of Earl's championing of Progressive thought; it wasn't until 1920 that women gained the right to vote nationally, signaling the lessening of the sort of male cronyism typified by both Otis and Earl, whatever the political differences or self dramatization involved.

|

| The dungeonlike hall, with another overpowering hearth |

Sorting out the three Emilys in Edwin's personal life is a tricky business. Edwin had married the first, née Runyon (born in California in August 1864 to a father who was a native of Kentucky), in 1884. The first Mrs. Earl seems to have been uninterested in the more intimate aspects of marriage, with the result being that after 16 years of frustration Edwin was able to obtain a divorce, charging Emily #1 with cruelty and desertion—these grounds often referring to a wife's sexual standoffishness—not long after they moved into 2425. There was next to no press mention of the split, though on February 15, 1901, the Herald, citing a possible reason for Earl's sale of his interests to Armour, reported that "the generally accepted opinion is that Earl wishes to have no further business troubles for some time, owing to his recent divorce suit." Enter the second Emily, a Louisvillian 10 years her predecessor's junior, who was spending the winter of 1901 in Los Angeles with her sister, Mrs. West Hughes (née Cora Jarvis). The wider orbit of the very social Dr. and Mrs. Hughes would have included the Earls...and so ensued the marriage of Edwin and 27-year-old Emily Jarvis on April 30, 1902, at the Hughes house on the corner of Flower and 23rd streets. Edwin turned 51 the year the couple's first child, William Jarvis, was born in 1904. The family then grew rapidly, with three boys and Emily #3 born between 1904 and 1908. Rather than becoming simply a ponderous monument to success, 2425 would now become a fascinating house for four young children to grow up in, at least until the 1920s.

Rather unexpectedly, following a 10-day illness over Christmas of 1918, possibly the Spanish flu, Edwin T. Earl died of a heart attack at home on the evening of January 2, 1919. It was then that the measure of the man was taken, revealing him to be less of a skunk and something of a hero in the history of Los Angeles. His obituaries, at least, even those in the Times, praised Earl as a leader and described the many expressions of regret at his death, including flower tributes sent by newsboys. Mayor Woodman ordered all flags on city buildings lowered to half-mast. There were eight active and 122 honorary pallbearers, lists which included every local marquee name of the era, from Governor Stephens to Mayor Woodman, Henry Huntington to Edward Doheny, Eli P. Clark to Hancock Banning, Arthur Letts to architect John Parkinson...and Harry Chandler of the Times.

|

| Commerce invades: As seen in the Times, December 6, 1930 |

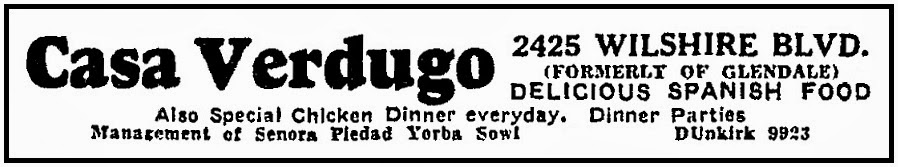

Emily Earl remained at 2425 Wilshire for a couple of years while the younger two of her four children finished high school. Now the owner of the Express, however, and ever the socialite, she was not given to staying at home. On July 27, 1921, at St. John's on Adams Street, she remarried. The groom was Washington banker William Eric Fowler; that fall, the family, including Jarvis, E. T. Jr., Emily, and Chaffee Earl, moved east, intending to maintain 2425 as a summer residence. While some family members maintained the house at least as a voting address, it seems to have been occupied principally by caretakers into the middle '30s, with at least one period during which it was given over to commercial enterprises. Piedad Yorba Sowl's famous Casa Verdugo restaurant, late of Glendale, spent at least the first few years of the decade in the house; by 1936 it housed doctors and dentists and an X-ray laboratory. The Los Angeles Art Association met at 2425 in the '40s. By now, the house was no doubt a bear to maintain, and the Earls were well out of it, especially with fashion having long since moved out to the newer western Los Angeles suburbs, Beverly Hills, and Pasadena.

|

| The modern library seems almost airy in comparison with the living room and hall |

Even if the neighborhood had been more stable, none of the Earl children seems to have had their father's drive—though he may have indeed been a tough act to follow—or Edwin's interest in maintaining 2425 as a family seat, which, at any rate, is usually more of a progenitor's priority. A sense of entitlement to a wider world may have shadowed the adulthoods of the younger Earls. Legal wrangling over Emily Fowler's estate continued for years. Invariably described as socialites and as little else, the Earl children managed to spend well and rack up quite a few marriages and divorces among themselves. Chaffee, the youngest, kept racehorses and, at 21, married a waitress, before long spending a little time in jail for failing to pay alimony; he later married and divorced a second time. "Pasadena socialite" Emily had at least two husbands, marrying her second, the actor Paul Gregory, in 1933 and divorcing him in 1940. Jarvis, who sold off some Earl properties for development, racked up a couple of wives, as did Earl Jr. In truth, the arc of the second-generations Earls was little different from many families whose fortunes derived from the industrial growth of late-19th-century America: money, opportunity, pleasure, glamour, with crashes along the way.

|

| With the address of 624 South Carondelet Street, the Earl carriage house was the home and bookstore of the celebrated Jake Zeitlin during the '40s. |

The Department of Building and Safety issued a demolition permit for 2425 on August 15, 1957. A Times article three days later reported that "Time scattered the family and the house fell into disuse. In 1938 it was sold for $99,000 to the county...." Los Angeles County used it as an annex to the Art Institute headquartered in Otis's house next door at 2401. While his exact tenure is unclear, the carriage house, addressed 624 South Carondelet, was rented from 1939 as the home and shop of bookseller, publisher, and poet Jake Zeitlin and his wife and business partner, Josephine Ver Brugge. The Zeitlins perhaps could be said to add an intellectual tone to the history of a house that was primarily the expression of more material pursuits.

Before the lot was cleared, the 58-year-old Earl house, born by fire, was poetically finished off by another one that broke out early on the morning of September 14. Up in flames went much of the house's carved paneling, some of wide redwood, that had been detached and stacked for removal.

§ § § § § § § § § §

At the end of its life, the Earl house was described by the Times in some detail. Seven fireplaces were noted; in an interview, a grandchild remembered many secret panels, for each of which, as a game, he was given a quarter for discovering. There were leaded windows throughout and an eight-foot-wide oak staircase. And, in a curiously modern detail, it seem that there were no bathtubs, but rather marble or tiled showers only, one for each bedroom. While the interior effect sounds rather ponderous and dark—perhaps even tomblike—rarely has a Los Angeles house been looked at so thoroughly and thoughtfully as it was by Richard Longstreth in his 1983 On the Edge of the World: Four Architects in San Francisco at the Turn of the Century:

"No realized design shows Coxhead's uninhibited use of classical precedent more fully.... The house was originally designed and built as a rambling, unobtrusive shingle pile, but fire wrought extensive damage shortly before completion. Coxhead then revised the scheme, retaining the informal plan and adding new elevations inside and out. In its final form, the Earl house, while still suggesting a rustic cottage, is fortified with a dense, tight wall of brick. An abstract, reductive simplicity enhances the exterior's strength, yet the effect is also made somewhat disquieting by the use of small, isolated pieces of ornament, the most conspicuous of which is a single Ionic column surrealistically supporting a tiny slice of entablature and pediment at the corner of the entrance porch.

"The stripped elevations also act as a foil for the decorative performance inside. Each room is a remote world, with such striking polarities of large and small scale, and ornate and simple embellishment, that it hardly seems like a house at all. In the living room a great scrolled pediment looms above the fireplace, suspended as if it were a trophy from Baalbek hung on the wall of an art academy. Its size is made even more outrageous by the low ceiling and flanking tiers of miniature orders. Across the room, Corinthian columns are isolated, again like fragments, punctuating curved bookshelves. The components are separated from their conventional context, and interact in an irregular space that is charged with contrasts between light and dark zones, plain and decorated surfaces.

"The hall is no less remarkable. Huge, classicizing motifs are placed in cavernous space with no direct source of natural light. The ceiling, which meets the walls without moldings, is penetrated by three recesses so large that the lower plane becomes little more than a series of inflated plaster beams. The wainscoting, composed of colossal panels topped by a garland, adds to the sense of confinement. At one end, the fireplace mantel projects outward in alternating slices of classical regalia and dressed blocks, rising precariously above a pair of Serlian consoles. While precedent can be found in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English interiors, the character of the heavy scale and agitated, compressed decorative elements ignores the stability inherent in classical tradition.

"Mayan architecture seems to have influenced Coxhead in the design of the room. Significantly, the resemblance to the plates of Frederick Catherwood's Views of the Ancient Monuments of Central America (1844), then the major pictorial reference on the subject, are more pronounced than the resemblance to actual buildings, which neither architect nor client had probably seen. Mayan sources also are suggested in abstract form in the library fireplace. Indeed, the entire room contrasts with the hall, being devoid of ornament and moldings. Bookcases, boxed beams, and wall panels are treated as planar surfaces joined at crisp, beveled corners, detailed in a manner similar to Irving Gill's simplest interiors of the next decade.The Earl house is the most sensational example of Coxhead's unorthodox sense of composition, and is the only occasion when he may have turned to non-Western sources for ideas.

"Unfortunately, nothing is known about Earl's role in the project. This self-made millionaire, who was an ardent promoter of the region's special character, must have wanted a design that no local architect could provide, for securing the services of an outsider was a highly unusual course for Southern Californians to take at the time. Did Earl share Coxhead's love of the unconventional, desiring a house so markedly different from the norm? Or was Coxhead simply reflecting the fantasy world that Angelenos were boosting, pulling out all the stops with a nouveau riche client who believed the design to be 'authentic'? Whatever the circumstances, Coxhead would never surpass the eccentricity displayed here."

|

| Today, the northeast corner of Wilshire and Carondelet is the playground for the Charles White Elementary School, the main building of which, at right, is on the site of the Otis house once at 2401 Wilshire. |

Illustrations: The Autry; Richard Longstreth/Google Books; Calisphere; LAT;

LAPL; Google Street View