3033 Wilshire Boulevard

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO WILSHIRE BOULEVARD, CLICK HERE

Oil man and real estate developer William Clay Price was one of the quieter participants in the meteoric rise of Los Angeles in the first decades of the 20th century. Although he worked and invested alongside more familiar names such as Charles A. Canfield, William G. Kerckhoff, Dwight Hart, Burton E. Green, Edward L. Doheny, Max Whittier, William Lacy, and Henry Huntington, Price's name is found frequently in century-old newspaper coverage but seldom in modern histories. Born in Savannah, Missouri, on March 30, 1850, to parents who started back east, Price married Emma DeEtte Eaton before he was 20; living up in Iowa and the father of a girl given her mother's middle name by the next year, it wasn't until after a move to Kansas and a second child was born there in September 1879 that Price continued his family's westward trajectory toward the inevitable California. Edward Price was just a few months old when his father moved them all to the 6,000-foot-high Nevada village of Tuscarora, where he would superintend a gold mine. Here—north of Elko and east of Winnemucca and Golconda—W. C. Price began building the real foundation of his Los Angeles success.

|

| As late as 1928, the north side of Wilshire from Lafayette Park to Vermont Avenue still appeared pleasantly suburban. Within the past year, however, the road had been widened and the famous Wilshire Special lamps had been installed. Across the street from 3033—at center above—excavations for Bullock's-Wilshire were underway; the store would open in September 1929 as would the 13-story Town House apartment building just to the east. The Prices were still in residence; almost all other houses on the boulevard had been given over to trade, including 3043, at this time the sales office for Dana Point. |

Perhaps Emma put her foot down firmly once she got a load of Tuscarora. By the next year W. C. had settled his family in Oakland, reachable within a reasonable amount of time from the distant mines he got more and more interested in; by 1884, his listing in the Oakland city directory would include an office address with the notation of "mining expert," indicating that he had quickly become more of an executive director of his operations, delegating authority for the actual removal of ore out in the hinterlands. In the usual way of forging alliances of power in the Gilded Age, local bank directorships and other boards became part of his résumé. A second daughter, Ruth, arrived in April 1888; with his family complete, Price may well have settled for a life of bourgeois comfort in Oakland, the end game for many a migrant to the West Coast. While certainly a solid enough city in which to build a home and career if not a town as exciting as the one across the bay, Price was a man of uncommon energy. Even if he had had ambitions to cross the water, San Francisco was developing by the '90s something of a more Eastern and hidebound social hierarchy; while the city may have been Paris compared to Oakland, it had no new literal fields of discovery that a man like W. C. Price required. Not only was Southern California famously more open—it was home to and near not only mines from which precious metals could be extracted, but wells from which much bigger fortunes could gush as well as the space for seemingly unlimited development, unlike the city at the tip of the northern peninsula. And dusty Los Angeles—much looked down the nose at by San Franciscans but with better weather—sat right on top of and in the middle of it all. For an initial domestic foray into the Southland, the Prices chose Pasadena, the only place there with even a hint of the genteel to outsiders. A fire in May 1899 at their East Oakland residence—and the subsequent looting of gold nuggets from it—might have clinched the deal; the Prices were renting a house on Fair Oaks Avenue by June 1900. But, as it turned out, Pasadena, with more than its share of tubercular Midwestern geriatrics, may have been even duller than Oakland and proven once and for all that Los Angeles itself was the future. No one who took a serious look at the turn-of-the-century city doubted it.

Every five years or so in Los Angeles—and at an even quicker pace as years went by—there was a new residential tract, its barren streets lined with palms fresh from the nursery, vying for the dollars of the affluent homebuilder. St. James Park in suburban southwesterly West Adams had opened in 1887, as men with the biggest purses were building florid Victorians set well back from the zanjas on South Figueroa and West Adams streets. The lots of Chester Place were delineated by 1899; once the city's first cable and electric street railways appeared in the late '80s, Westlake and what is today called Pico-Union opened up for the building of vast swaths of bungalows and big upper-middle-class houses. With so much land, it was a free-for-all: It would be decades before the seeker of the best Los Angeles neighborhood knew for certain whether to go to the southwest of downtown, northerly to eastern Hollywood, or more due west of First and Main. One strange millionaire, famous for his Van Dyke and socialist cant, knew that directly toward the Pacific was the obvious choice. While West Adams had by the aughts become an established, beautifully landscaped district, in parts very like Pasadena, some of the more adventurous saw Gaylord Wilshire's four-block boulevard down the middle of property he'd bought on the other side of Westlake Park in 1895 as the answer. Somehow anticipating the automobile age, Wilshire banned public transportation on his new thoroughfare. Extended not long after opening beyond the bend of the original city grid where Hoover Street met Lafayette Park, the boulevard acquired its cachet almost instantly. Wilshire was the perfect fit for an energetic visionary like W. C. Price, who had made inroads with the local establishment in typical short order. On August 1, 1904, a headline in the real estate section of the Herald reported that W. C. PRICE BUYS LARGE RESIDENCE SITE ON WILSHIRE BOULEVARD AND WILL BUILD HOME; on the same day, the Times noted that the 170-by-180-foot lot was at the northwest corner of Wilshire and Virgil in the West End University Addition tract. Price chose one of the top residential architects of the day to build his steep-roofed stone-and-shingle house, one with commissions completed or coming all over Pasadena and Los Angeles by plutocrats such as Andrew McNally, Isaac Newton Van Nuys, Frederick Hastings Rindge, and William Edmund Ramsay. Frederick L. Roehrig's design was an amalgam of English and Craftsman styles just approaching their heights of popularity, inarguably modern after the Victorian age while at the same time suggesting antiquity and permanence to Angelenos wary of a new and barren landscape and neighbors hailing from everywhere back east. Given his many business ventures during these years, it is likely that W. C. left matters of taste to Emma; in any case, the Prices—with just Ruth, approaching high school, left at home—were settled into 3033 Wilshire Boulevard by the spring of 1905.

|

| Work on the new town of Beverly Hills began as soon as the Rodeo Land and Water Company was formed in January 1906. That fall large advertisements appeared, this one in the Times announcing the development's opening on October 22. Early on, the full name was reserved for the upland residential section, with the commercial center generally referred to as "Beverly." Wilshire Boulevard, still a dirt road from at least Western Avenue, was soon to extend, much quicker than anyone imagined, many miles past Gaylord Wilshire's original four blocks between Westlake and Sunset parks (now called MacArthur and Lafayette parks). |

Meanwhile, William C. Price was quietly participating in more deals than can be counted. There were gold and copper mines such as the Pompeii and "Old Maid" claims in Arizona, there were oil wells from Bakersfield to Mexico, there were sugar beets, and there was land. With various partners, dozens of oil syndicates were formed, each requiring a new name: There was the Amalgamated, the Cleveland, the Arcturus, the Submarine, the Revenue, the Salt Lake, the Midway, the Traders Union, and the Wellman, to name a few. There was also the fabled Mexican Oil Company that had been chartered in 1901 with Doheny, Kerckhoff, Hart, Lacy, Herman Hellman, and California Club cronies such as Ezra Stinson and Almon Maginnis. As for land from which only increasing value would be mined rather than elements, W. C., this time with Emma as partner, bought speculative parcels to flip in his new neighborhood. And, in late 1904, with eyes to the future acquired from the father of Wilshire Boulevard, the partners in the newly formed Amalgamated Oil Company—Price, Kerckhoff, Whittier, Green, Canfield, and Huntington among them—took an option on several thousand acres described two years later as "adjoining the town of Sherman [West Hollywood], extending to the new golf grounds of the Country club, north to the foothills and south to the Rindge land." The spread had seen cattle in the Mexican era, sheep in the 1860s, and lima beans under the ownership since the '80s of the families of Henry Hammel and Andrew Denker. The Times confirmed the sale on January 6, 1906, reporting that the new organization would be called the Rodeo Land and Water Company. During the time frame of its option, it seems that Amalgamated Oil, having failed to find petroleum on the property, came up with an alternative plan for what had earlier been named El Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas. Realizing the potential value of its being naturally well supplied with water during a period of extended drought that had William Mulholland and Fred Eaton already exploring the Owens Valley, Price and his partners decided to develop what the Herald called a town of "high-class residences" on from one to five acres. This was embryonic Beverly Hills.

|

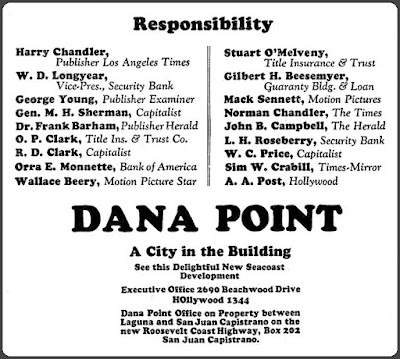

| W. C. Price was investing in Southern California real estate until the end of his life. The development of Dana Point brought together some of the biggest names in Los Angeles in a joint effort of the downtown establishment and Hollywood. An early sales office of the venture was in the old Fisher house at 3043, just west of the Price residence. Bankers Willis D. Longyear and Orra Monnette were Price's fellow Wilshire homeowners (3555, 3101 respectively). From the Times, October 26, 1927. |

While many of his associates would eventually move to Beverly Hills, and the establishment's Los Angeles Country Club would relocate from Pico Street to adjacent property soon after the town was formed, W. C. Price stayed put on Wilshire Boulevard. There are indications that he may have divested his interest in the new development before it opened officially in October 1906; perhaps he saw better long-term prospects closer to home. By the time the lucrative commercial future of the avenue came into focus after A. W. Ross's plan for the Miracle Mile emerged in the early '20s, Price was in his 70s; while remaining active in business, participating in the development of Dana Point as well as serving as a director of the United States Bank and on the board of the Wilshire District Chamber of Commerce that was overseeing the boulevard's dramatic widening and its transition from residential to commercial, his health began to decline. The end came at home on May 21, 1929, just months before the Chamber's success was crowned by the opening of the magnificent Bullock's-Wilshire on September 26. Despite its 241-foot tower dwarfing the Price house across the street, Emma stayed at 3033, continuing her involvement with such cultural organizations as the Welsh Eisteddfod Society, which sponsored a week-long (imagine) festival of "songs, recitations, readings and accomplishments in the field of manual arts." By the time she died at home on October 13, 1933, she and her house had become a last vestige of Gaylord Wilshire's vision of a residential boulevard formed 38 years before. The Department of Building and Safety issued a demolition permit for 3033 on April 16, 1935.

|

| It is unclear as to the commercial uses 3033 may have had after Emma Price's death in October 1933, but the less-than-30-year-old house had little time to stand. A Union Oil station had replaced it by 1938. In contrast to Wilshire Boulevard's consistent reputation for grandeur, this 1949 streetscape more accurately reflects the avenue's largely hodgepodge development. Despite filling stations sitting across the street from both the towering Bullock's- Wilshire and I. Magnin (in the distance), the stores long maintained their luxury images. The story of the early commercial development that replaced the houses of Wilshire Boulevard is here. |

Illustrations: Private Collection; LAT; USCDL; LAPL