2401 Wilshire Boulevard

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO WILSHIRE BOULEVARD, CLICK HERE

According to the militaristic fantasy world he made for himself, Harrison Gray Otis insisted on being referred to as "The Colonel" well after his service in the Union Army and as "The General" after a non-combat tour of duty in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War. The house he built at 2401 Wilshire Boulevard in 1897 was "The Bivouac"; he called the downtown headquarters of his Los Angeles Times "The Fortress," which it proved not to be. For all his personal noisomeness and juvenile gameplaying, "The General" was nevertheless a tireless if autocratic booster of the rising city of Los Angeles, a man who must be taken in the context of his time and regarded with some measure of respect for his efforts on behalf of the city. It might also be said that Otis promoted Wilshire Boulevard, being as he was a "launch customer" for Gaylord Wilshire's new subdivision, comprising four blocks between Westlake (MacArthur) and Sunset (Lafayette) parks, bisected by the eponymous fledgling boulevard. Otis's rather delicate Bivouac was built on the first south-facing lot on Wilshire, its east side overlooking Westlake Park across Park View Street.

|

| Modesty no doubt prevented the General from covering every square inch of his uniform with medals. |

The life of Harrison Gray Otis is well chronicled; excellent is PBS's Inventing LA: The Chandlers and Their Times. Some contemporaries did not think much of the man, including California's 23rd governor, Hiram Johnson, who excoriated Otis in a famous 1910 campaign speech in Los Angeles: "He sits there in his senile dementia with gangrene heart and rotting brain, grimacing at every reform, chattering impotently at all the things that are decent, frothing, fuming, violently gibbering, going down to his grave in snarling infamy. This man Otis is the one blot on the banner of southern California; he is the bar sinister on your escutcheon. My friends, he is the one thing that all Californians look at when, in looking at southern California, they see anything that its disgraceful, depraved, corrupt, crooked, and putrescent—that," Johnson concluded mercifully, "that is Harrison Gray Otis!" As for The Bivouac, it is perhaps a clue to countervailing forces within the man that rather than directing that it be converted to cash for his heirs after his death in 1917, he instead bequeathed it to Los Angeles County, his will stipulating that it "be used for the advancement of the arts." The County started the Otis Art Institute the next year; 2425 Wilshire next door was acquired by the school after refrigerator-car developer Edwin Tobias Earl died in 1919. The Earl house was another of the early houses built on Wilshire Boulevard; both it and The Bivouac were gone by 1957 to make room for a bigger school facility. The Fortress and The Bivouac—in other words, the rabidly anti-union General—had been targets in the infamous 1910 bombing that destroyed the headquarters of the Times. The "infernal machine" (as timed explosive devices were referred to once upon a time) placed in the bushes at The Bivouac was defused before it went off; so too, was the ticking present of dynamite sent through the mail to the ever-popular General three years later. An odd stone folly remained from Otis's day as a presence on the art school grounds; according to an interesting footnote in Privileged Son: Otis Chandler and The Rise and Fall of the L.A. Times Dynasty by Dennis McDougal, this replica of The Fortress "had been made from [the bombed building's] rubble and stood on the grounds of the General's former home for nearly 40 years" before being broken up, the pieces given to Otis students.

|

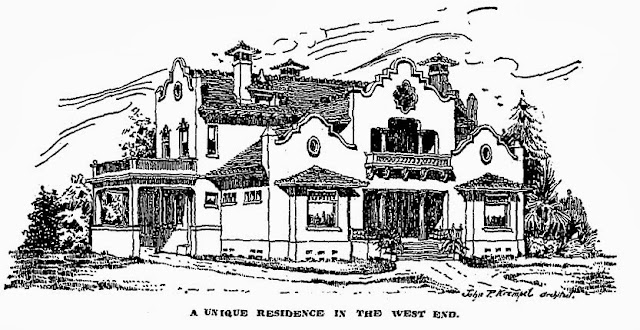

Views of the Harrison Gray Otis house at the foot of Gaylord Wilshire's original boulevard, circa 1900. The carriage house is seen above; Edwin T. Earl's house at 2425 Wilshire is seen next door to the west below. While his house is certainly attractive, one might not have expected quite so fussy a design to have pleased the blustery General. The side bays with large picture windows serve to disguise the actual size of the house. Wilshire Boulevard is yet to be paved. |

|

| On the first visit of an American president to California, William McKinley spent the night of May 8, 1901—four months before he was assassinated in Buffalo—at The Bivouac. He would spend the next evening at a reception in his honor at the home of his old Ohio friend Homer Laughlin at 666 West Adams Street. The view above is of 2401's east end from the edge of Westlake Park. |

|

A view of the front portico east toward Westlake Park reveals delicate detailing of the Otis house,

somewhat at odds with the bellicose personality of its owner, and the carriage-size front drive. |

|

Rare interior views of the Bivouac: Above, the entrance hall; below, the upstairs landing. As some children would later hang model airplanes from their bedroom ceilings, the General chose to hang guns. |

|

The beginning of the end of The Bivouac, 1956. The Department of Building and Safety had issued permits for its demolition on January 4. A number of different signs were on the lawn over the years, reflecting the graphics of successive eras. It's always interesting to be reminded of what's behind the stucco—here, Mission Revival is revealed as stage set. |

|

| The configuration of the Otis Art Institute campus combining 2401 and the Edwin Earl house at 2425 Wilshire Boulevard, 1951. |

|

| Built in 1912 on the grounds of the Bivouac, Otis's memorial to the bombed Fortress used stones from the rubble and topped it with a representation of the bronze eagle rescued from the ruins. |

|

The Times building intact, before the eagle and a wing were added; below, after the 1910 bombing |

Illustrations: LAPL; U.S. Militaria Forum; LAT; USCDL; HDL; CDL;

The Art Institute of Chicago; Otis College of Art and Design